Brooks Robinson Represented the Best of Sports

The legendary third baseman passed away this week, leaving a legacy far larger than baseball

When I was 7 years old, my dad took me to Cooperstown, NY. I was a baseball fanatic, no doubt because my dad was one too, and so it was a natural pilgrimage. We saw the Hall of Fame, stopping at all our favorite players’ plaques. We bought baseball cards. And one day, there was a clinic with baseball legends at the historic Doubleday Field in the center of town. I had brought my mitt, of course, so my dad signed me up.

The “legends” were mainly MLB journeymen, Jack Lazorko from the Mariners, Bob Patterson from the Angels, each former player taking a station and teaching us about the game. They showed us how to warm up before pitching, complete with a warning to not start trying to spin a curveball until we were old enough. They showed us how to run the bases. And then, we went to a station where we learned how to field a groundball.

Brooks Robinson was running that station. He told us to square up. Get in front of the ball. Then he tossed a grounder to us and we tossed it back.

Robinson died this week, and although he is undoubtedly the greatest defensive third basemen and most important Baltimore Oriole of all time, what’s striking reading tributes to “Brooksie” is that baseball doesn’t seem to be his legacy. What people remember most is his kindness and generosity. I wasn’t the only one who learned to play baseball from Robinson; it was the type of thing he did all the time. “If you lived in Baltimore and never shook Brooksie’s hand, it’s because you never tried,” wrote Dave Sheinin in the Washington Post.

Growing up, Robinson lived a gee-wiz, bubble gum type of life. In Little Rock, Arkansas, he learned to hit using a sawed off that his father, who worked at a bakery, had fashioned for him. Brooks was naturally lefthanded, but in second grade, he broke his left arm and didn’t want to stop playing catch. So he learned to play righty. It’s one of baseball history’s great what-if’s: if he stayed as a lefty, he never could have played third base.

In high school, he picked up a football and after one toss, was reportedly named the starting quarterback, though he preferred baseball. He took girls on dates to the malt shop. He had a paper route. When he graduated, the high school yearbook named him, “Best All Around,” and for $4,000, he chose to sign with the fledging Baltimore Orioles, who had lost 100 games the year prior, instead of inking an identical deal with the reigning World Series champion New York Giants. He made his Big-League debut at only 18.

At first, he couldn’t hit—not for power, not for contact. But boy, could he play defense. As the great Joe Posnanski described:

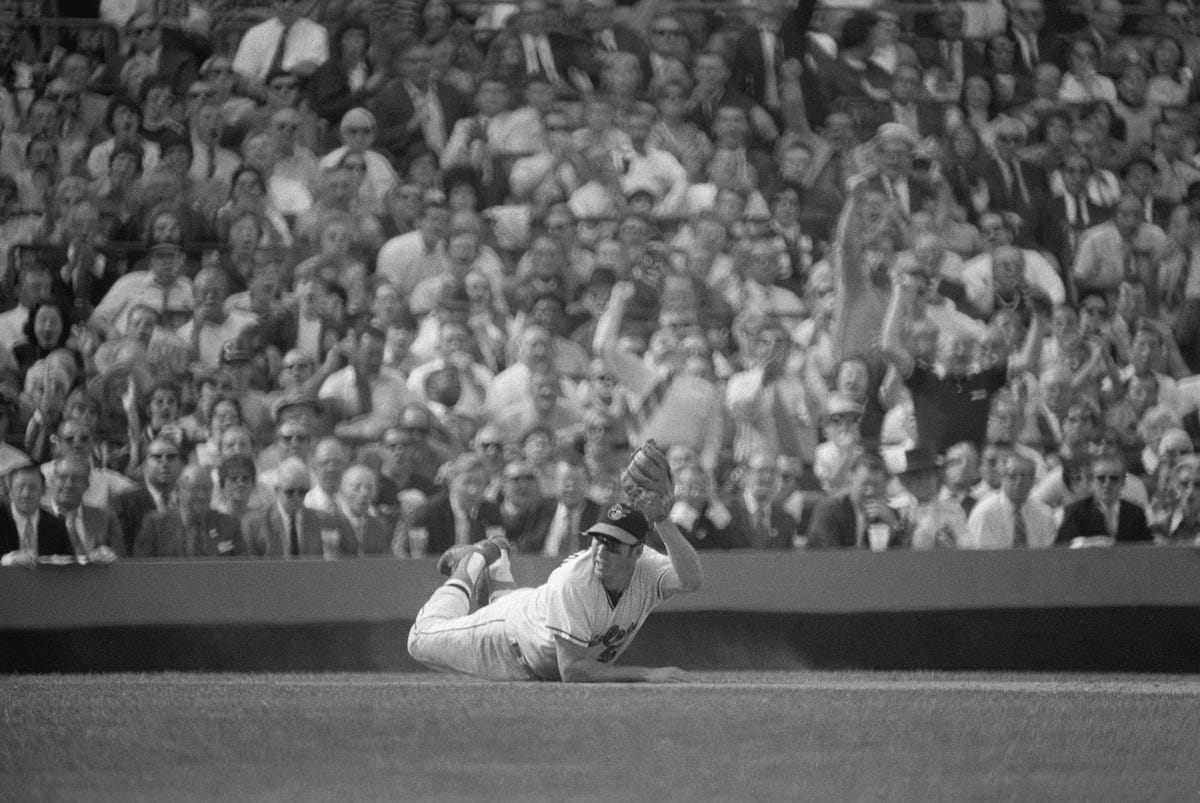

At third base, he was Nureyev. He was Astaire. He was Wallenda. He was Sawchuck. He was Slydini. No matter how hard a ball was hit down the line, no matter how wickedly it was hit into the hole, no matter what sort of bad hop the ball might take, Brooks Robinson somehow was there. He had a way of contorting his body so that the ball always ended up in his glove. It would then magically appear in his right hand, and while he did not have a cannon arm, he had the quickest release imaginable and he could throw falling backward, falling sideways, falling forward, across his body, and somehow, no matter how he threw it, the ball ended up chest-high in the first baseman’s glove.

The bat soon followed, and Brooks won two World Series, an MVP, and made an astonishing 18 All-Star Games. As always, though, it wasn’t just about baseball. He called Frank Robinson, who would become the MLB’s first Black manager after his Hall of Fame playing career, his “brother.” The two Robinsons would later take road trips together, and Brooks would sometimes stop the car in the middle of the street to chat with strangers who recognized them. ESPN’s Tim Kurkijan wrote this week, that Brooks Robinson was, “the single kindest person I've ever met in 45 years of covering baseball.”

Throughout his entire 23-year playing career, he made less than $1 million, earning just $35,000 during his 1970 MVP campaign. Hearing about Brooks’ financial troubles, a local lawyer named Ron Shapiro offered to represent him as a client. Shapiro would go on to become a powerful sports agent, and Brooks was so appreciative that he promised he would give Shapiro one of his 16 Gold Glove awards. Shapiro refused. Then, one day, his door rang. A Gold Glove trophy was sitting on the porch; Robinson had just run away.

For 23 seasons, Robinson played for Baltimore, winning the city its first World Series. In the final year of his career, the team in the middle of a pennant race, he told the team to cut him; a younger, livelier bat was just what the team needed for the last stretch of the pennant race. That’s the kind of person Robinson was; it was always bigger than him.

Athletes like Robinson are role-models, yes, but they’re something more than that. Brooks Robinson became a type of civic institution. He taught generations of Baltimoreans how to treat others, how to work hard, how to give back. He once said that it seemed like every day, he would receive letters with pictures of newborns named “Brooks.” Every time, he would send back a signed photo with a note: “Brooks, I’m honored you have my name. I hope to say hello to you some day.”

When they grew up, he might have taught them how to field a grounder, too.

🎞️ Did you miss our new series, Skin in the Game, with Dr. Ibram X. Kendi on ESPN+? Check it out here.

🎸 Former R.E.M. members have made a supergroup that only sings songs about baseball? Louisa Thomas is on the case for The New Yorker.

🧡 You don’t want to miss this crazy story about a Tennessee student’s Ferris Bueller day at the 1998 National Championship which wound up with him leading the team out of the tunnel. You can’t make this stuff up.

🔥 Hawaii’s entrance out of the tunnel is the best thing you’ll see all day.