ROS Rewind: A Q&A With the First Woman to Run the Boston Marathon

On the morning of the Boston Marathon, we're revisiting our interview with runner and activist Kathrine Switzer

Happy Monday, everybody!

This morning, 30,000 runners will converge in Hopkinton, MA, before running the famous Boston Marathon. Across the area, schools and businesses will be closed to celebrate Patriots’ Day, and the whole city will line its streets to cheer on the runners. It’s one of sports’ great traditions—and in fact, it’s the world’s oldest annual marathon. But for much of its history, women weren’t allowed to compete.

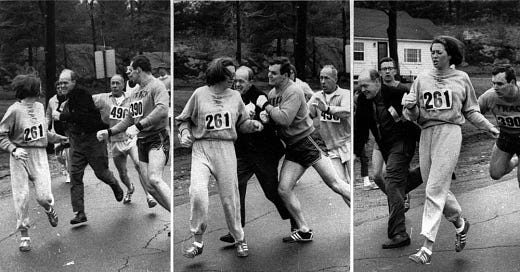

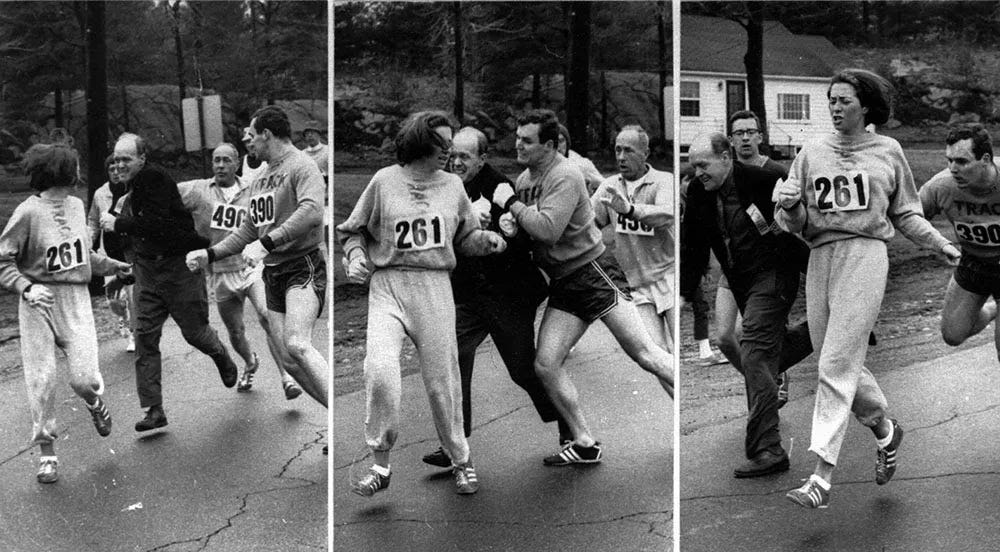

That all changed in 1967, when Kathrine Switzer, then a 20-year-old Syracuse student, became the first woman to officially run the Boston Marathon. A few miles into the race, one of the marathon’s officials jumped off a car and attacked Switzer, trying to get her to withdraw. But Switzer kept running and eventually finished the race. In the years that followed, she successfully lobbied the IOC to add the women’s marathon to the 1984 Olympics, founded 261 Fearless, and has never stopped running. In fact, just yesterday, the 76-year-old Switzer ran a 5K in Boston.

In 2020, I spoke with Switzer about her history-making run and the role of sports in her life for this newsletter. “A run every day is like praying,” she told me over a Zoom from New Zealand, where she lives part time. “Then, when we go to the marathon, it’s like we’ve gone to Mecca.”

Since many of you have just joined us, and because it’s one of my favorite interviews we’ve done for The Word, today felt like a perfect time to revisit this Q&A. If you like it, we might continue to resurface some stories from our archive when it’s appropriate. So read on, enjoy, and let me know what you think!

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Joe Levin: Can you set the stage a little bit for 1967? What was the attitude towards female runners at the time?

Kathrine Switzer: The myth prevailing then about women running was that a woman would turn into a man, get big legs, grow hair on her chest, maybe even turn into a lesbian. They also thought that her uterus would fall out, and she would never be able to have children. Of course, I thought all of this was nonsense. I had heard those myths all through my childhood when I was out running when I was 12 and 13 years old. People said, “You shouldn’t do that. You’re going to turn into a boy. You’re going to get big legs.”

JL: How did you get involved with running against that backdrop?

KS: I went to Syracuse University, and if you can imagine this, there were no intercollegiate sports there for women. Men had 25 sports, all with scholarships. Women had playdates. But I was a runner, and I felt I could run by myself. So I went to train with the men’s cross-country team, and the male runners were incredible. They totally welcomed me, even though I couldn’t yet keep up with them.

A volunteer coach, who was in his 50s and an ex-marathoner, started helping me. I told him that one day, I wanted to run a marathon, and he said, “A woman cannot possibly run a marathon distance.” We argued, and he said, “Look, if you showed me in practice that a woman could do it, I’d be the first person to take you to the Boston Marathon.” So from there, I had this plan.

After months of training, we went through the rulebook. There were no rules that said women are not allowed. They just assumed that a woman couldn’t and wouldn’t run. So, I registered and signed my name, “K.V. Switzer,” which was a crunch point later because they thought I was a man. But I was officially entered.

What he had been led to believe is that, even though he was out there running with me every day and telling me I was really good and really improving, he was afraid that somehow he was going to be responsible for damaging me. In practice the day we finally ran the 26.2 miles, when we were finishing it, he said, “I can’t believe how good you look. You really look strong.” And I said, “I don’t think this is the full distance. Let’s run another five miles.” So we ran 31 miles, and he passed out at the end of the workout. When he came to, he looked at me and said, “Women have hidden potential in endurance and stamina.”

Later, he said, “You have to now sign up for the race.” And I said, “Well, why can’t we just go and jump in and join the race unofficially?” And he said, “Are you kidding? This is the Boston Marathon. It’s second only to the Olympic Games. You’re a registered athlete. You don’t mess around with those guys in Boston. You’ve got to fill out the entry form.”

We went through the rulebook. There were no rules that said women are not allowed. They just assumed a woman couldn’t and wouldn’t run. So, I registered and signed my name “K.V. Switzer,” which was a crunch point later because they thought I was a man. But I was officially entered. I probably would have been ignored if I had just run without registering, but I was trying to follow the rules and do the right thing, which is the irony of it.

Once I got serious and ran over three miles a day, I stopped going to church. I realized it was because I felt closer to God and the universe out in nature than I ever did inside with a group of people.

-Kathrine Switzer

JL: Did you decide to run the Boston Marathon as an act of protest to prove that women could, in fact, run it? Or was it just something that you wanted to do for yourself?

I went to Boston because that was my reward for showing my coach in practice that I could do the distance. So it was, “Okay, now we’re going to go with our friends, and we’re going to run the Boston Marathon. It’s going to be great.” I wanted to comport myself well. I wanted to look good. I wanted to be able to finish strong. And that’s why I did the 31 miles in practice, so I had no doubt about that. But no, it was not was not a political reason at all—until the official attacked me. And then it became political. It became very political.

JL: What are you thinking when the official tried to grab you in the middle of the race?

KS: I told my coach I was going to finish it on my hands and my knees if I had to, because women were always being told they were barging into places where they’re not welcome, and they can’t do it. I knew I could do it. And I knew—as embarrassed and scared as I was—if I dropped out, everybody would say, “See? She’s just here for a joke.”

JL: In that moment when the official grabs you, and you realize “I have to finish this race,” you go from someone who’s trying to finish a marathon to a symbol for all of this other stuff. Did the weight of that hit you immediately? Or did it take a while to sink in?

KS: The global import of it didn’t come for quite some time. My instinct was, “I’ve just got to finish this race, because he doesn’t believe I’m serious. And I am serious.” So, the focus became that. But I’ve got to tell you, suddenly, I was very, very tired after the incident. Anytime you have a near miss with something, you lose all that adrenaline, and it wasn’t just me. It was the whole team—my coach, my companions from the cross country team. Everybody was drained. So for about 10 kilometers we ran along, just feeling like, “Ugh.” Then all of a sudden, we came out of the trough and got better and better. I finished the race feeling very, very strong.

At 21 miles, I stopped being angry with the official. I’d murdered him in my mind up to that point every way a person could be murdered. Then, it just went. The anger went, and I realized it’s not his fault. I thought that this guy is a product of his time, just as surely as women are not here because they’re afraid, he’s a product of his time. I can forget that. I can forgive him, and I thought he’ll grow up, he’s ignorant, that’s his problem, and he’ll figure that out. But it’s my job now to figure out how to get women the opportunity so they are not afraid, and they will do something bold and experience this wonderful feeling I have of freedom and destiny and transcendence. And I really wanted to give them that. But how, though? How?

I was thinking of that and thinking of that, and finally, it all boils down for me. If you run for hours and hours and hours, your thoughts condense and condense. I realized two things when I crossed the finish line: One, I’m going to become a better athlete, because my coach said, “Let’s just slow down to make sure we absolutely finish.” We finished in four hours and 20 minutes. I knew I was going to be pilloried for that, because that was considered a jogging time back in the 60s. I knew I could be better, but I didn’t know how much better. I was physiologically curious about what I could do.

The second thing I wanted to do, though, is create those opportunities for women. And I didn’t know what it looked like at that point.

JL: Did you ever speak with the official again?

KS: I forgave him right away. But we women got to work, legislated, campaigned, and changed the rules and got officially welcomed into the Boston Marathon in 1972. By then, he had to admit us to the race, legally. He was really steamed about it. He said, “If girls are going to run my race, they’re going to have to meet the men’s qualifying standard.” We said, “Okay,” and the time was 3:30. It was pretty tough at the time, but eight of us could do it. And the eight of us were there. Afterwards, he said, “Why—didn’t they run well? I’m so surprised,” as if he hadn’t noticed for the five years we’d been there running.

Then he came up to me, and on the starting line of the race the next year, he gave me a big kiss. He was a Scot, and he turned me around to this bank of TV cameras. He said, “Come on, lass. Let’s get a wee bit of notoriety.” He never said he was sorry, but that was his way. We really became good friends. We would do interviews like this together, panels and things like that.

I went to visit him a few hours before he died. People say, “Whoa, that’s a lot of forgiveness.” And I say, “You know what? Life’s really way too short to carry that around.” They say, “Yeah, but still.” I say, “No, no, no. How can you not love somebody who has not only made the worst thing in your life become the best thing in your life; who has not only changed your life but changed therefore, millions of women’s lives?; And frankly, someone who has given not only the women’s rights movement but the civil rights movement one of the greatest photographs in history?” I said, “You’ve got to love him.”

He was irascible right up to the end. The last thing he said to me was, “I made you famous, lass.”

JL: When did you realize how important your run was?

When I realized the import of this certainly wasn’t at the finish line, because I was greeted by a bunch of irascible journalists who had been standing out in the snow and sleet for four hours waiting for me to finish. They were really cross, really irritated, and I was very sharp with them. One guy said to me, “This is just a one off deal. You’ll never run another marathon again, right?”

I was only 20. I said, “You know what? One day you’re going to read about a little old lady who’s 80 years old who drops dead on a training run in Central Park.” I said, “It’s going to be me.”

JL: And how many marathons have you run?

KS: 42. But the most important of those, believe it or not, after ‘67 was 2017. I ran on the 50th anniversary, and I was the only woman who’s ever run a marathon 50 years after she first ran one. That’s not because I’m great. It’s because of how few women ran 50 years ago. That’s all that means. It’s testimony to good health and keeping fit. I honor my body greatly, and I get mad when I do something wrong.

Anyway, at midnight that night of the race, we were driving back to Syracuse, and we stopped on the thruway, getting coffee and ice cream to stay awake because we had classes and work the next day. When we walked into the cafe, all the newspapers were out on the newsstands, and all of them were covered with the picture of this incident. The next day in the journalism school library, everything—even the front page of the Asahi Shimbun in Japan—had the picture.

I knew when I saw the newspapers that things were going to change. I could have walked away and gone home and sat on my hands, but my dad had always taught me when you do something, you’ve got to finish it and take responsibility for it. I always firmly believed that, so I picked it up and have been responsible for it for the rest of my life.

JL: That’s an incredible amount of responsibility to take on as a 20-year-old.

KS: It was, but at the time, the enormity of it hadn’t quite affected me. It was very, very hard to get other women on board. Women were very nervous about it. I learned sponsorship, I learned marketing, I wrote business proposals and eventually wrote one to Avon cosmetics, the world’s largest cosmetics company. They loved how I thought. They said, “We’ll never do anything with running, but we’d love for you to work for us.” I said, “That’s good enough for me.”

I started working for them, and I begged them to do one running event. It was so successful that we went back to my proposal and launched this pilot series, then a huge program, eventually, in 27 countries, 400 races, with a million women running.

And the best part was we got the women’s marathon in the Olympic Games. That was 1984. It took us eight years to get it approved, but that’s warp speed for the IOC. If we had followed their protocol, we wouldn’t have gotten the marathon until 2012. Getting it in ‘84, it just leaped generations. It was phenomenal. It changed the landscape because it was on TV. 2.2 billion people watched it on TV, and everybody knows how far 42.2 kilometers, or 26.2 miles, is. They know it’s far. It changed a lot of notions. In fact, some people have said that it was as important as giving women the right to vote, because it was the physical equivalent of that intellectual and social acceptance that came in 1920 following the 19th Amendment.

JL: What role does running play in your life now?

KS: Everybody that participates in any kind of walking or running activity knows that repetition and rhythmic breathing create a relaxed and altered state and take you out of your space. If you concentrate on your breathing and what you’re doing, you leave the garbage of the world behind, and you can focus then on what matters, whether they’re problems or issues of the heart or a type of spiritual enlightenment. Certainly, I use this as my time for praying or meditation. But mostly as I get older, it’s a time for gratitude and a time to be a part of nature.

I remember when I was training really, really hard, twice a day, I said, “There’s going to come a time in my life when I don’t have to do this anymore.” And then when that time came in my life, I realized that the run was actually the best part of my day. It wasn’t a labor. Once I decided I didn’t have to prove myself anymore, it wasn’t a labor. It was a privilege.

I remember quite distinctly. Once I got serious and ran over three miles a day, I stopped going to church. I realized it was because I felt closer to God and the universe out in nature than I ever did inside with a group of people. There’s a lot to be said for the community of an organized religion. I understand religion and church from that point of view. But one of the best things for us as runners, indeed, is when we get together for a race or fun run together, we have our tribe, our community. That’s going to church.

I have often said that a run every day is like praying. Then, when we go to the marathon, it’s like we’ve gone to Mecca. It’s like a pilgrimage. Once in the marathon itself, once in a long race itself, we’re there together. We’re pilgrims trying to cover this distance together for whatever cause we believe in. That’s one reason why charities are very important now in running. People feel that running has given them so much that they want to also contribute back.

JL: Can you tell me about your nonprofit, 261 Fearless?

KS: My dream is to get every woman on the planet an opportunity to put one foot in front of the other and walk or run. Basically, what we’re doing is creating globally a series of community safe clubs—women only—where women take the hand of another woman who’s fearful, and gets her into a safe place for an hour a week to walk, run, and have that sense of empowerment and sense of destiny that can come from running.

The myths that prevailed back when I ran the marathon in 1967, honestly still prevail hugely in many countries and cultures today. It’s astonishing that this kind of thinking still exists. It’s born out of fear and superstition, but it also has to do with biology. It’s really only been for the last 50, 60 years that women have been able to control their biology. Sports have played a huge role in helping us to show the world that we are very strong and very tough, also.

Running, for women, is transformational. Whether that’s a religious experience or not, I’m not sure, but it is at least partially. It’s a religious experience and partially a physiological experience and emotional experience as well.

JL: What does that name, 261 Fearless, mean?

KS: 261 was my bib number in Boston. When I ran away from the official, he tried to tear off my bib on the back. He missed it, but he cut the corner. So he ripped that one, and in the race, it kept flapping. I remember the feeling of it on my back.

Over the years, suddenly, people began writing to me and said, “I’m wearing 10,942 on my first New York City Marathon tomorrow, but I wanted you to see what I was wearing on my back,” and they’d have 261 on their back. Or they’d ink it on their arm. And I thought, “Isn’t that nice?”

Then they started sending me pictures of their tattoos. So then I had to think that if somebody is tattooing 261, what does it mean to them? They kept using the word, “fearless.” I suddenly understood that they were relating to the story of being told they weren’t good enough, or they didn’t belong, or they were the wrong color or the wrong religion or nationality. They went out and ran anyway. And then, they felt fearless. They said, “Well, I can do this.” Through the vehicle of running, we get women to feel fearless.